Obscenity and Art I Know It When I See It

In the final edition of the Obscenity Case Files serial, nosotros discussed the Pope five. Illinois conclusion and how it impacted the Miller Examination for identifying obscene material, which is not protected by the First Amendment. In this edition, we'll take a await at Jacobellis five. Ohio, a decision that pre-dates Miller v. California, to shed some light on the infamous "I know it when I see it" linguistic communication.

Knowing Information technology When Y'all See It

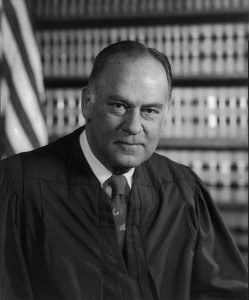

In his concurring opinion in the 1964 Jacobellis v. Ohio case, Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart delivered what has get the well-nigh well-known line related to the detection of "hard-cadre" pornography: the infamous "I know it when I see it." statement.

"I have reached the determination . . . that under the First and Fourteenth Amendments criminal laws in this surface area are constitutionally limited to difficult-cadre pornography. I shall non today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to exist embraced inside that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I encounter it, and the move film involved in this case is non that. "

As far as unintentionally comical lines in judicial opinions go, "I know information technology when I see it" is as good equally it gets. The phrase immediately invokes images of blackness-robed Supreme Court justices pouring over pornographic magazines and screening "adult" movies, paying special attention to whether or not the materials tickle their "prurient interests." Yous'd be hard pressed to observe a First Amendment analyst or constitutional police professor who doesn't have at least one "I know it when I see it" joke on manus.

Justice Stewart, the story goes, developed his eye for smut when he was stationed as a Navy lieutenant in Casablanca during World State of war II. While at that place, he had taken a gander at the locally produced pornography his men brought back to his ship. As this quote from his former law clerk shows, Stewart relied on his acquaintance with Moroccan pornography when he consort his belief that he would know when he was seeing pornography and so hard-core that it should be considered obscene:

"After several days reviewing with the other court members the materials related to the '63 Term pornographic materials, Justice Stewart came to the office for a Saturday stint of opinion writing. I was there solitary when he arrived, and we visited together to discuss his reaction to the instance. . . . I had been a Marines officeholder; he a Navy officer. We discussed our experiences with material nosotros had seen during our military careers, and discovered we had both seen materials we considered at the time to be pornographic, simply this conclusion was arrived at somewhat intuitively. Nosotros agreed that "we know information technology when we see it," simply that farther analysis was hard. The justice went dorsum to his part, and presently thereafter produced a draft concurring opinion, which has by now become somewhat famous. I am sure he never expected, intended, or desired notoriety for this element of his work." (source)

The Lovers

Jacobellis five. Ohio (1964) was the case Justice Stewart and his law clerk were hammering away at when they came to their "I know it when I run across it" epiphanies.

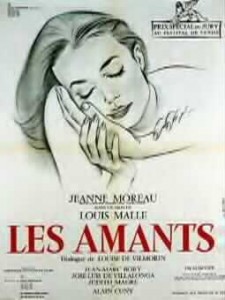

Nico Jacobellis, the defendant in the case, was the director of an art-house theater in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. Ohio government had taken consequence with his public exhibition of the film The Lovers (Les Amants) at his theater, convicted him of criminal charges and fined him $ii,500. According to Ohio authorities, The Lovers — a French film about a woman involved in infidelity who rediscovers human love — contained subject matter prohibited by Ohio's obscenity statutes. After the Supreme Court of Ohio upheld Jacobellis' conviction, the case ended upwards before the U.S. Supreme Courtroom.

The Supreme Court ultimately decided The Lovers warranted Outset Amendment protection and reversed Jacobellis' conviction. The Court, however, could not concord on a rationale for determining what constituted prohibitively obscene subject matter. Despite a majority of the Justices concluding that Jacobellis' conviction should exist reversed, the Court'south final ruling was fragmented. It included 1 majority opinion and four concurring opinions (none supported by more than than two Justices) in which each author attempted to clarify what he believed was an advisable characterization of how the First Amendment should apply to allegedly obscene material.

The reasoning in the opinions supporting reversal ranged from Justice Hugo Black's position that the Outset Amendment does not permit censorship of any kind (joined by Justice William O. Douglas) to Justice Brennan'southward reluctance to conclude that The Lovers was "utterly without redeeming social importance" (joined by Justice Goldberg).

Past far, the near famous of the Court's opinions was Stewart's concurrence, which contained the "I know it when I see it" language reproduced to a higher place.

Aftermath

Post Jacobellis, the Supreme Court held a scattered position on what constituted obscene speech. It wasn't until the 1973 Miller five. California decision and its implementation of the 3-prong test for obscenity that the Court officially made the motility to a more objective rationale. Although Justice Stewart's reluctance to fix a "vivid line" rule for flushing out hard-cadre pornography was much better for the development of obscenity jurisprudence than the Court creating a listing of actions or words that are per-se obscene, information technology is hard to see how society would do good from select authorisation figures basing criminal convictions on their power to subjectively "know when they meet" unprotected speech.

Current obscenity police force may non be perfect, but the Court'southward adoption of an objective standard for determining a works' merit or artistic value, rather than an "I know it when I see it" standard, benefits comic book creators and retailers. At the very least, it guarantees the relevance of the work they create and sell will not be decided based solely on what diverse say-so figures have known or seen.

Delight help support CBLDF'south important Commencement Amendment work and reporting on bug such equally this by making a donation or becoming a member of the CBLDF!

Rick Marshall is an attorney who recently finished piece of work on a legal chief's degree in Intellectual Property law at the George Washington University Law School. Cheque out his musings on the intersection of music and copyright police at his website www.copynoise.com.

Source: http://cbldf.org/about-us/case-files/obscenity-case-files/obscenity-case-files-jacobellis-v-ohio-i-know-it-when-i-see-it/

0 Response to "Obscenity and Art I Know It When I See It"

Post a Comment